False Friends: 20 Words in Spanish That Are Tricky | donQuijote

Have you ever ventured to use a word in another language without making sure of its meaning first? The answer is probably yes. And it’s also very likely that you have felt embarrassed at least once because you accidently said something completely different or even nonsense.

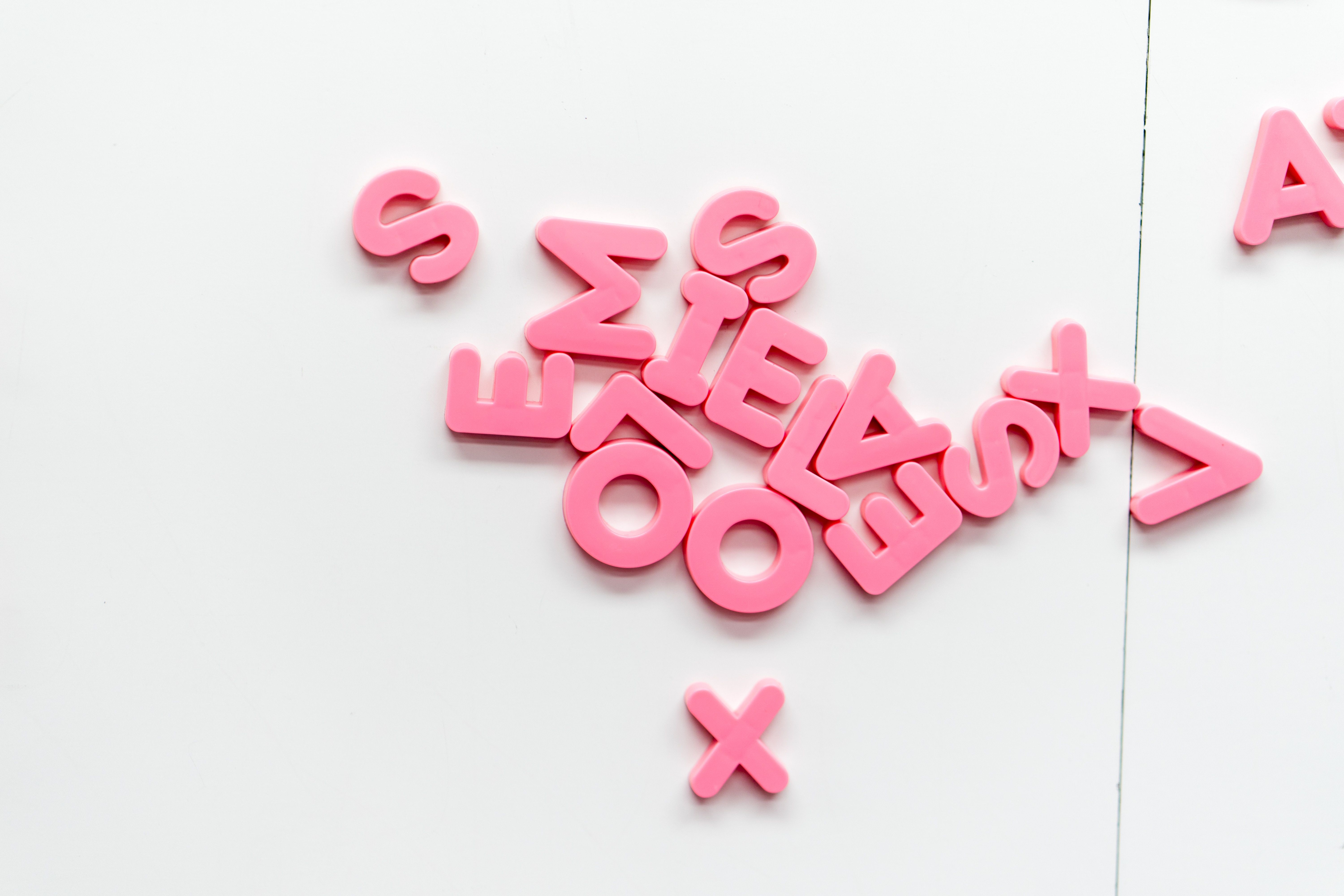

In today's post, we bring you a compilation of 20 false friends (also called “cognates”) so that next time, appearances won’t fool you. Ready?

Click here to read the post in Spanish.

What are false friends?

False friends are words in another language that sound similar to a word in our language but have a different meaning. As the term indicates, false friends can play dirty tricks on us if we trust them blindly just because they sound or look familiar. While it is true that these words often have a common etymology, they evolved differently, giving rise to distinct meanings.

The term “false friend” comes from the French faux-ami and was introduced by Koessler and Derocquigny in their book Les faux-amis ou les trahisons du vocabulaire anglais (False Friends, or, the Treacheries of English Vocabulary) published in 1928.

List of 20 English - Spanish false friends

1. Actualmente does not mean “actually” (never mind how much we insist):

• Actualmente: currently

• Actually: en realidad

2. In Spanish, if someone gives you an aviso, they are not giving a piece of advice:

• Aviso: notice, warning

• Advice: consejo, recomendación

3. Atender does not mean "attend" (although they are similar):

• Atender: pay attention, help

• Attend: asistir, estar presente

4. In Spanish, when they say that somebody is bizarro, it does not mean that they are strange nor bizarre:

• Bizarro: brave, courageous

• Bizarre: raro, extraño

5. Moreover, Spanish speakers don’t use carpetas to make the floor warmer in winter:

• Carpeta: folder

• Carpet: alfombra, moqueta

6. The term comodidad does not really have anything to do with commodity:

• Comodidad: amenity, comfort

• Commodity: product, mercancía

7. In addition, a complemento is not something to say thank you for:

• Complemento: accessory

• Compliment: cumplido, halago

8. If a Spanish speaker says that they are constipado, they are not being too honest:

• Constipado: have a cold

• Constipated: extreñido

9. In Spanish, discutir is a bit stronger than “discuss”:

• Discutir: argue, have an argument

• Discuss: hablar, exponer, debatir

10. An embarazada has nothing to be ashamed of:

• Embarazada: pregnant

• Embarrassed: avergonzado/-ada

11. Eventualmente is a frequency adverb for Spanish speakers:

• Eventualmente: occasionally

• Eventually: al final, después de todo

12. Éxito is not a way nor passage out, but something to be proud of:

• Éxito: success

• Exit: salida

13. Although it also refers to size, largo is not the same as “large”:

• Largo: long

• Large: grande

14. Spanish people don’t go to the librería to study:

• Librería: bookstore

• Library: biblioteca

15. In Spanish, when somebody pretende something, you can usually trust them:

• Pretender: hope, expect

• Pretend: fingir, simular

16. Realizar has a lot to do with dreaming for Spanish speakers:

• Realizar: make, fulfill

•Realize: darse cuenta

17. If somebody tells you they’re sensible in Spanish, you’d probably need to be tactful:

• Sensible (Spanish): sensitive

• Sensible (English): sensato

18. In Spain, a suburbio is not a nice place to live in:

• Suburbio: slum, ghetto

• Suburb: barrio residencial, afueras

19. When a Spanish speaker says something is terrorífico, they are not normally very happy:

• Terrorífico: terrifying, horrific

• Terrific: genial, espectacular

20. And finally, a tópico is not a subject of discussion, but a word related to stereotypes:

• Tópico: cliché

• Topic: tema

Perhaps this short list of Spanish false friends has given you a new appreciation for professional translators. Think of the disastrous consequences of telling a client you’ve found a new property that’s ideally located in a suburbio! Let this be a reminder (or a warning!) that if you ever need language translation services, it’s important to work with professionals to avoid embarrassing mistakes that may ruin your reputation!

At don Quijote, we hope not only that you’ve enjoyed today’s post, but also that you find it useful and are spared some awkward situations. We encourage you to share this post with your true friends to save them from falling into the trap of false friends when speaking a different language.